The Monetary Commonality

Bitcoin uses electricity to deliver superior monetary technology

A popular critique of Bitcoin is that its mining process uses too much energy. Critical articles list numbers that purport to show a huge use of electricity comparable to that of a small country. Specific amounts aside, though, the subtext is that such energy is mostly being wasted because Bitcoin is just bait for speculators or worse. It not only consumes copious electricity but does so for no good reason.

We will first discuss some points regarding the interpretation of Bitcoin’s energy use itself. After this, the bulk of the discussion will focus on what Bitcoin uses energy for. How does Bitcoin compare to other monetary technologies both in terms of the quality of what it produces and the total resources that the respective processes consume? Looking at both costs and performance together in a comparative-systems context should produce a more balanced approach.

Several problems with Bitcoin-as-energy-hog reasoning are typically present. First is a lack of understanding of what the energy is being used for and why this is important, particularly in a larger context of society and history. A critic who suggests, for example, that the less energy-intensive proof-of-stake approach of some other cryptocurrencies is an obvious substitute for Bitcoin’s proof-of-work design reveals that they have not grasped the key element of why Bitcoin is revolutionary as a globe-spanning monetary technology—the proof-of-work design itself.

Critics tend to present Bitcoin energy use without conveying what the system accomplishes. They do not usually compare it with fair estimates of the total energy drains of other monetary technologies in current use summed on a global basis. For example, the total energy cost of Bitcoin and the Lightning network that operates on top of it would have to be compared not only to the energy costs of fiat money, banking, payment, and associated regulatory systems in one country, but to the combined costs of all such systems over the entire world. The exchange rate frictions and uncertainties of trading across multiple national fiat money systems would have to be added, in contrast to the globally unitary nature of Bitcoin. Then the incalculable costs to everyone of recurrent business cycles and inflations that follow from fiat central banking systems would have to be somehow reflected in the quest for fair comparison.

Bitcoin’s electricity use for mining is simple and transparent, which is why an estimate of it can be easily added up. However, the total costs of—and collateral damages from—its major competing monetary systems are multifaceted, opaque, and deep.

Such factors would have to be estimated in relation to scale of use now, but also for realistic scale of potential future uses. Bitcoin, along with the Lightning bitcoin payment network—as well as other existing card-payment technologies that can conduct transactions denominated in bitcoin units just as well as they conduct transactions denominated in euros or yen—can scale without difficulty to transmit any amount of value that needs transmitting over the entire world.

Another major problem with the Bitcoin-as-energy-hog critique is that energy, and most of all generated electricity, is not homogenous. It varies in value depending on where and when it is produced and how far it must be distributed. A bucket of water in the middle of Lake Victoria is not the same economic good as a bucket of water in the middle of the Sahara Desert. Likewise, electricity in one time and place can be and often is a different economic good than electricity elsewhere. Electricity is produced live and for the most part must be used live, the closer to the source the better due to transmission loss. A given flow of electricity in the mountains of Kazakhstan is in no way comparable to the same flow of electricity in New York City in August—where, incidentally, expensive electricity regularly powers and cools just some of the many massive offices of the existing fiat-based financial system.

Comparing aggregated units of electricity consumption without regard to location, time, and cost is misleading. Each unit of energy, and especially electricity, is unique in time and place and cannot be compared as if it were everywhere and always the same interchangeable good.

Unlike many other electricity uses, Bitcoin mining is relatively mobile (and would be even more so without arbitrary legal restrictions). Mining can be performed where energy is cheapest and in least demand. It can also be switched off in minutes during peak grid loads. This contrasts with the conventional use of variable-load coal or gas power plants that can take hours to bring fully online to meet peak grid demand. Bitcoin brings to the grid the option of quickly switching off one source of demand during peak local loads rather than having to inefficiently increase supply for short phases.

Transmission loss means there are benefits to producing electricity closer to where demand is. However, Bitcoin mining can locate itself anywhere cheaper energy is or can be developed. Bitcoin mining can enable and support energy projects that would not be economical to develop or maintain without the presence of a nearby Bitcoin mine as the baseline power buyer of last resort. Bitcoin mining can spring up in places where potential energy is abundant, but nothing much else is. There is no need to “regulate” such practices into existence. Miners have a natural incentive to locate near relatively remote cheap electricity sources, not expensive ones. Of course, they must also consider other factors, such as legal climate and average local temperatures.

Moreover, in conventional energy-production systems, a great deal of energy is simply wasted on a regular basis. Beyond electrical transmission loss due to distances between production and consumption sites, flare gas from oil drilling is another example of routine energy loss, one where Bitcoin mining has already proven a practical way to take up slack right at the energy-production site, turning waste into revenue. One of the things that Bitcoin mining entrepreneurship supports is alertness to ways to make use of energy resources that are otherwise wasted or minimally valued.

Which brings us to our main topic. Bitcoin mining does use energy. So does all human activity. A key question then is: What does Bitcoin use energy for and how does this compare to the costs and benefits of other monetary technologies that likewise consume energy?

If someone believes a given activity is useless or harmful, they will believe that no amount of energy ought to be dedicated to carrying it out. If someone believes a given activity is essential to the further advancement of civilization, then even “high” energy use will seem a bargain.

Power for what?

Bitcoin is a new kind of monetary system. It creates and establishes a monetary unit and provides a settlement system for transferring control of these units among system users. Other systems working on top of the Bitcoin network tend to be better at transferring control of smaller amounts denominated in bitcoin more quickly and efficiently than directly on chain.

What does any monetary system have to accomplish to function and how can it do so? How does Bitcoin use energy to do this in a unique new way?

Several characteristics have been identified as essential for a money to have, such as fungibility, durability, and divisibility. In this discussion, we will highlight a key issue for any monetary technology. It must have some mechanisms for 1) limiting the production of monetary units and 2) conveying to users of said money that such limitations are likely to remain effective into the future.

The monetary commonality is that all such systems must fulfill these functions in some way. Bitcoin does so in an entirely novel way. And Bitcoin must be compared to other monetary technologies on a fair basis in terms of both costs and performance. In other words, how effective is each monetary technology at accomplishing these functions relative to the resources it consumes?

In the history of economic thought, several traditions of monetary value theory have ascribed the one true essence of money mainly to one factor, namely, that factor which each school most favors in its treatment of the subject. Each also partially or totally dismisses the other factors—namely, the ones competing schools cite as being most essential. The credit theory argues that money originates as debt and is debt. The state theory argues that money originates as a created creature of the state and remains one now. The commodity theory argues that money originates as a commodity and was one—before losing its roots in a step-by-step corruption process that left us with modern fiat money as a sad remnant.

Bitcoin does not seem to fit any of these models. It entails no creditor/debtor relations, only direct and irreversible final transfers. A sovereign does not issue or manage it, rather, it surprises sovereigns when they notice that it has not only already arisen, but functions without them. It is not dug out of the ground and traded as a coin processed from a physical commodity such as gold or silver. Indeed, it lacks any traditional hard commodity linkage anywhere in its history.

Bitcoin can appear at first, from each of these traditional schools of thought as…nothing. And by the way, it cannot possibly “work” in a monetary role, since it lacks the one true factor that gives money value—according to each respective school of thought. It’s not a commodity. It’s not state-backed. It’s not debt. So it cannot be money.

Yet, it remains fully operational as a monetary network, is used daily in some very money-like ways, and could easily be imagined to operate in even more money-like ways in the possible future.

Rather than such dismissals representing a problem with Bitcoin, what if this pattern indicates a fresh and unforeseen challenge for these constellations of monetary thought? Fortunately, it appears that one factor—the requirement that unit production be somehow limited and that the integrity and continued operation of such limits are ascertainable by money users—ties together the varied and at-times seemingly contradictory elements that each school has touted as the one true explainer.

Conflicting accounts of the nature and origin of money

Some theorists of money have argued that linkage to a commodity at origin is the real reason that any money initially gained value (commodity theory). This was at least so in the past. Even today, there is a great deal of gold allegedly located in central bank vaults. The old “metalism” considered value to be “in” metals. Gold and silver are money. More nuanced versions argue that the scarcity of such metals naturally limited new unit output. Pure fiat money now exists, but, according to this view, could not have begun without having taken over from previous commodity monies when state/bank alliance members defaulted on their obligations to redeem paper certificates and account entries for metal.

Others claim “the real” reason for monetary value has always and everywhere been the support of rulers (state theory). “Money is a creature of the state.” It always was, is, and must be. Even if many state-issued coins so happen to have been made of copper, silver, or gold, this was a merely incidental historical artifact. And thankfully, we are told, such old material “fetters,” the metals themselves, were finally abandoned in modern times, leaving only the pure will of the sovereign (and its banking partners), which was always the one true factor anyway. What happened in times past, we are told, was that the state’s fiat certifications had been stamped on metal coins instead of printed on paper slips. The fiat essence of the money was always there; it is merely more efficient now for the sovereign to ink its imprimatur on paper than it had been to stamp it onto rare metals. What a waste that had been, we are told.

Still others interpret the existence of primitive favor-swapping, tribal gift practices, temple debt ledgers, tally sticks, credit money, and running bar tabs to imply that all money must be explained as “really” gaining its value from credit relations (credit theory). “Money is credit/debt,” according to this approach, the evolved medium for swapping favors in a post-primitive-band context.

But here we find another inconvenient oddity much like the one we observed for the state theory. Much as fiat stamps supposedly just happen to have been printed on precious metal coins, so historical credit ledger entries also typically just happen to have been denominated in units of some commodity such as weights of silver or heads of livestock. This supposed mere coincidence of debt-ledgers being denominated in classical commodity-money units somehow does not give much pause to these theorists as they press on with their thesis that the true essence of money-ness comes not from commodity-ness or even state-ness so much as from credit-ness.

A new interpretive challenge

Despite rivalries among these approaches, there are grounds for thinking that each makes some valid points yet has not gotten to a common root. The populist metalists erred toward thinking that value was “in” precious metals, while state and credit theorists rightly scorned metalists for intrinsicism, but ironically made a similar type of error.

Metalist, state, and credit theory thought processes alike can each be seen as advancing a form of monetary creationism. Creationism purports to explain a phenomenon, not by explaining it directly, but by positing a creator or an origin story. The problem is that the various creationisms point to something antecedent that then also requires explaining, without having necessarily explained the thing itself.

Metalist creationism says: “The value is in the metal. The metal creates the value of money.” Metal talks, directly as it were.

State creationism says: “Rulers create money and that explains its value.” Money’s value is to be found in the approval of the prince or in the acceptance practices of the treasury. Money has value because the state decrees it.

According to credit theorists, the source of money’s value originated in tribal practices of swapping favors. Later roots came from centralized practices such as keeping temple debt ledgers. Pointing to archaic lending practices supposedly explains the value of money without explaining what exactly it is that is being lent. The history of lending creates the value of money. A misty essence of the accrual of favors and services is somehow being transmitted through the monetary unit.

One might easily err in a similar way with Bitcoin. Satoshi Nakamoto created it…therefore…

Therefore nothing. Bitcoin’s nominal originator had the good sense to launch the system, see it through a few early hiccups, and then vanish before it had gained hardly any market exchange value—leaving Bitcoin to be judged by what it is and does, not on who created it.

The monetary commonality

On the usual lists of monetary characteristics, one sees items such as fungibility and divisibility and these are certainly necessary qualities for a money. The word “scarcity” is also there. Yet scarce has several technical meanings that differ between general economic theory (non-superabundant goods), property theory (rival goods), and casual everyday use (there’s less than I would like there to be). In a monetary context, moreover, scarce is used in yet a fourth sense, one rather specific: the quality of having constraints on the production of new units.

This sense of scarcity alludes to some method for restricting monetary unit production. This factor is common to all monetary technologies. Some combination of such constraints on production has in each case generated public perceptions that monetary units are likely to maintain their purchasing power from yesterday to today and into tomorrow. The alleged relative predominance of one such method relative to others characterizes the different types of money and some of the different schools of thought on money.

Such constraints may be viewed in two aspects: 1) the constraints themselves and 2) the readiness and accuracy with which users can ascertain the nature of such constraints and monitor their efficacy. There must be both objective efficacy in limiting unit production and ways for people to ascertain that these constraints continue to operate over time.

Limitations on unit production are of two types. First, money users must be sufficiently convinced that money producers will limit their own output at least to some reasonable degree—for some reason. Second, illicit counterfeiting cannot be so easy and widespread that it could have a significant impact on purchasing power.

Thus, it must be shown that 1) money producers face either some objective limits and/or self-imposed discipline and 2) this restraint cannot be easily neutralized by third-party counterfeiters. A sufficient failure of any monetary system to address these factors would either degrade or shatter the purchasing power of its units.

Both objective and intersubjectively ascertainable

For any monetary system to work, it must be possible for users to agree that certain facts are or are not a certain way based on a common standard of evidence. For example, users need some way to confirm and agree that a given specimen is one of the units that it is supposed to be. One person might think the paper he has is a dollar; another might discover it is counterfeit. One person might think she has a solid gold bar; another might find that it is a gold-coated tungsten bar.

This same requirement extends beyond counterfeiting to the general public understanding of a unit’s supply characteristics—an understanding of how changes to its stock come about and how significant and variable such changes are likely to be. If people thought the total supply of a given money would double tomorrow, for any reason, this perception would impact their cash-balance decisions today.

However, this is more than a mere “shared illusion.” An illusion cannot be shared if there is no path through which such alleged illusion-sharing can function over time. If the perception about the doubling of money had been accurate and the supply in fact doubled the following day, the purchasing power of the unit would become substantially lower than it would have otherwise been, regardless of any illusions.

These results would follow even apart from changes in expectations about money-production volume. An actual net increase in the number of units in the possession of money users would set in motion a series of effects, even if most people had not heard the thunder of the money-dropping helicopters.

Precious metal coins

With precious-metal coins, the objective factors limiting supply—and informing the public understanding of such limits—included technical fields such as stamp design, metallurgy, and coin testing. These worked to make counterfeiting individual coins, and debasing all coins, harder to hide and more costly to undertake. Such knowledge helped people distinguish specimens as authentic or fake and helped secure the value of all units in circulation.

Metal content specifications alter minting cost structure. The general understanding that precious metals are limited and costly and that a certain type of coin was claimed to contain a certain amount of metal bore on the likelihood that the coin would be produced in either greater or lesser quantities.

The form and appearance of coins, including their stamps, also influenced these perceptions. The old debate as to whether it was metal content or fiat stamps that “really” solely determined the value and choice of money presents a false-choice dichotomy. The relative contributions of these and other factors differed by time and place. Wherever both factors were present, both influenced the choices of the money-using public and the purchasing power of the monetary unit. Some value perception was attached to the metal, some to the “brand” certification.

None of this follows directly from so-called “inherent” properties of the units, whether metal content, princely stamp, or status as debt representation. It follows from both actual unit-production characteristics and general perceptions of the likely relative purchasing power and liquidity of the units. Various factors go into forming those perceptions. The interpretive question is what those factors are in each time and place. Both actual and perceived supply characteristics contribute.

Thus, the historical value of a gold coin bearing a ruler’s bust should not be simplified to either a pure commodity money (the metal) or a pure fiat money (the stamp on the coin). Some combination of each factor likely contributed to both regulating unit production and informing the public’s general understanding of the quality of such regulation.

Fiat notes and bank-credit money

With fiat money notes, people understand that counterfeiters will be prosecuted, and that the treasury or central bank will attempt to regulate the production of new units in some supposedly reasonable way based on their legislated authority. These methods support user perceptions that not only is counterfeiting suppressed, but the quantity of new units from the money producer itself is also constrained. The government is in charge and has this handled.

Notes of one-trillion denomination could be mass-produced starting tomorrow if those responsible decided doing this was in their own interests. It so happens that they most often do not. Why not?

Monetary destruction is not in the interests of a ruling class that relies on a steadily inflating (value-losing) monetary unit to extract advantages to itself away from the general public. The banking system delivers a flow of special-interest benefits to its orchestrators, promoters, and their cronies, and does so in a relatively stealthy way. It must be kept running and ideally its wealth-transferring functions not too widely noticed, for elites naturally desire that such lucrative though unethical transfers continue indefinitely. When such a system truly crashes, as in the case of hyperinflation, even elites lose out, not only the mass of ordinary citizens.

This elite interest in maintaining a functioning exploitation system via the instrument of fiat money likewise pertains to the most common form of modern money—electronic account entries at commercial banks. This “modern” bank-credit money is created at the wave of a banker’s pen in the granting of a loan. What is “lent,” however, is nothing other than an alteration of the digits in the bank’s accounting system. Nevertheless, despite the appearance of “free money,” such largesse cannot continue without restriction, for if it did, the system itself would soon degrade and potentially collapse. The game would be up. What methods are used to prevent this?

The public understanding of such “fountain-pen money” is murky. It is easier to cite the more obvious inflation-promoting activities of central banks and treasuries than to grasp the concept of commercial banks making up free money on the spot.

But fountain-pen money, too, has its own peculiar sources of supply restriction. Among factors limiting the production of commercial bank-credit units is the fact that those issuing them must belong to a state-orchestrated cartel, follow this cartel’s evolving rules and guidelines, and operate in the context of ever-changing official interest rates and other policies. If they deviate too far, they risk ejection from the club. Central banks, banker associations, and other regulators, set and modify these rules and membership requirements. Not just anyone can set up shop and start “loaning” made-up account credits without unfavorable attention from higher-level inflation orchestrators. The continuous mass-expropriation entailed in the fiat inflation system must be kept sustainable, lest the masses begin to complain excessively of their lot, which threatens to occur from time to time.

As with fiat paper money, so with bank-credit money, a key part of what restricts the addition of new units is a legal status that is backed up by force and threats, right up to the military might of the issuing nation. Institutional force reserves to cartel members the privilege of granting made-up loans and receiving fees and interest payments for this service. All others must be forcibly prevented from joining. Even those who have managed to get into the exclusive club must be restrained from exceeding the club’s current restrictions. The sustainability of the cartel must be maintained, and so inflation of new units must remain sufficiently coordinated to avoid a loss of confidence and a breakdown of the whole scheme.

Such is the quality and ethical foundation of some of the methods by which central banks and banking cartels attempt to regulate modern fiat money unit production.

Bitcoin’s unit-production constraints partly define what it is

In diametric contrast, Bitcoin both enforces and reveals its unit-production constraints in entirely new ways far superior to any of the preceding methods. What has formerly been done with metallurgy, certifications, centralized recordkeeping, legal power and threats, and cartel coordination, is now done with an open-source protocol for a peer-to-peer network engaged in cryptographic verification using proof of work.

Compared with previous methods of limiting unit production, Bitcoin prevents counterfeiting almost entirely. The network ignores invalid transactions. And while it is simple to start a new altcoin chain, units on any such chain cannot be passed off as bitcoin (BTC) units because they have no place on the Bitcoin block chain, something that is simple to verify any time without charge. Non-BTC coins can also carry some tradable value, but even market participants who trade in such units do not believe that the altcoin units are directly interchangeable with units of BTC, which latter would be the threshold for successful counterfeiting.

Bitcoin defeats arbitrary inflation from within by specifying its new-unit production schedule as an integral part of the system itself. The unit is one 21-millionth of the total possible stock of such units. More precisely, the unit the Bitcoin network uses is a satoshi, of which 2.1 quadrillion can ever be produced; what is called a bitcoin is actually a unit of 100mn satoshis.

A defined and inalterable unit-production schedule is central to what defines the Bitcoin network’s identity. Bitcoin not only objectively restricts the production of new satoshis via the algorithmic enforcement of the world’s largest computational network, it also provides a transparent and free means for anyone to verify all unit production right up to the present minutes.

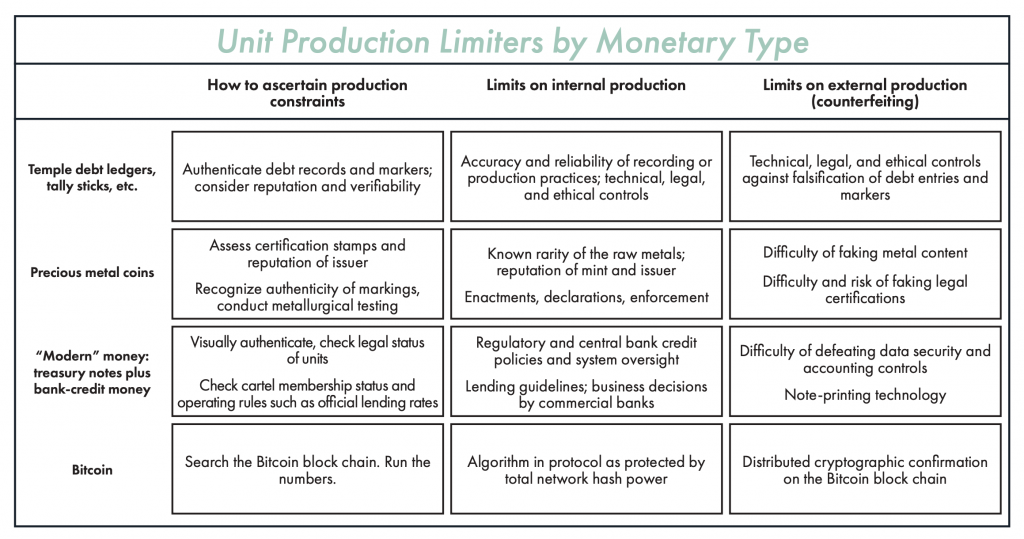

The following table summarizes for each of several monetary technologies, constraints on production and counterfeiting, and how users can ascertain these constraints.

Unit production limiters by monetary type:

Among all monetary technologies, Bitcoin stands out as being clear, objective, transparent, and predictable. The methods it offers by which users can verify its unit-production constraints are unprecedented in their reliability and near-universal accessibility. Anyone can audit the entire money supply and production rate any time. And the total supply of units is not only knowable now, but also predictable well into the future to a degree never before possible.

The security of the system is built on its proof-of-work mining network. Energy is one of the major inputs to this process, alongside mining rigs, server farm space, cooling systems, and legal-system predictability. In contrast, modern monetary systems are inflationary schemes that require a vast governmental and quasi-governmental-commercial apparatus of enforcement to persist.

Modern monetary and banking systems consume enormous resources. This includes the cost structure of the entire banking and payment industries and their regulatory overseers and enforcers, with all their branches, offices, headquarters, employees, server farms, security systems, and so on, not forgetting each year’s heating and cooling bills for all these sites over the entire earth.

The resources consumed to support this conventional authoritarian basis for monetary value regulation are herculean. To this must be added the resources wasted across entire economies as all market participants constantly adjust to recurring economic booms and crashes resulting from manipulation of the money supply and interest rates by monetary central planners. Most ordinary citizens suffer a loss of resources from inflation all the time, which only becomes more noticeable when inflation is even higher than it normally is.

Ironically, the cyclical speculative environment this system produces is one factor behind the volatility of the fiat-money price of bitcoin, as leveraged players find in it yet another “risk play,” which becomes one part of their desperate search for ways to counter the never-ending but variable-speed degradation of the value of fiat-money units.

Bitcoin provides a very simple deal from a monetary-technology standpoint. Some electricity is consumed to run mining rigs. These operations naturally tend to gravitate toward anywhere that energy is cheaper (other things being equal), which tends to also be where energy is in lesser demand from competing uses. This creates a steady incentive to maintain, develop, or tap marginal energy resources when possible (temperatures, reliability, security, and local legal and business climates permitting). For this cost, Bitcoin provides, by a very wide margin, the most objective, predictable, and transparent monetary unit production schedule of any monetary system ever devised and there is no close second.

Conclusion

Money has value in that money users assess a monetary unit as having both liquidity and purchasing power now and a relatively high chance of maintaining these qualities over timespans they each consider relevant. Commodity content definitions, state stamps of approval and acceptance, a cartelized banking system, credit relationships, and most recently cryptographic relationships on a peer-to-peer network, are all elements that have operated in different ways, sometimes blended, to 1) limit monetary-unit production, both by primary money producers and counterfeiters, and 2) do so in ways that inform public perceptions of the ongoing operation of such constraints.

A mere “money-illusion” is insufficient to explain the value of money. Production constraints must limit unit production and these limits must be to a sufficient degree ascertainable by money users. On both counts, Bitcoin is far superior to all preceding monetary technologies that have accomplished these same functions using different methods.

Bitcoin has demonstrated a completely new way to implement unit-production constraints and a new, highly accessible way for anyone to confirm that such constraints remain in effect. It has eliminated counterfeiting from without and made remarkable and unprecedented steps to render inflating from within either impossible, or if ever attempted, spectacularly transparent. With Bitcoin, far more than with any of the monetary technologies that originated before it or that continue to operate next to it, the general public is wholly capable of knowing, verifying, and predicting the full supply characteristics of the monetary unit.

To discuss Bitcoin’s energy use in a balanced way, this revolutionary value as a new monetary technology must be recognized. In addition, the total resource use of any competing monetary technology must be tallied for a fair cost comparison. Bitcoin’s objective and easily measurable energy use must be viewed next to some estimate of the vast, varied, and harder-to-sum energy use from relevant shares of the conventional military, legal, banking, and payment system apparatus that currently supports and orchestrates—and lives off of—the fiat money system. Moreover, some estimate must be added for associated collateral damages from such systems, including easy-money funding for wars and systematic attacks on civil liberties, steady and sometimes high inflation, and periodic economic booms and crises.

Bitcoin operates as a monetary technology in a way that is vastly superior to the way the currently entrenched fiat system operates. Meanwhile, its specific use of relatively easily measured amounts of electricity, which naturally tends toward being drawn from lower-energy-cost locations, compares favorably to the massive cost and waste structure that underpins the operations of Bitcoin’s major remaining monetary-technology competitor.

Konrad S. Graf

@KonradSGraf

11 July 2022