To the Socialists of All Parties

An Introduction to The Bitcoin Times: Austrian Edition

The hardest thing to understand about bitcoin actually has very little to do with bitcoin. It has to do with money. Bitcoin is hard to understand because money is hard to understand, and very few people have ever questioned money at a fundamental level; what it is, why it exists or how to evaluate one medium relative to another. Every economic assumption or model builds on top of the existence of money as a given; it is an assumption taken for granted that then serves as the foundation to do all other economic calculations. At least in the developed world, money has always just existed and for the most part worked. Yet very few have ever consciously considered why the dollar in their pocket or the deposit in their bank account is accepted by hundreds of millions of people in return for real world value. People learn about economics or finance in school, but not money. It might just be the most consequential tool and innovation ever developed by man, but just about everything is taught except for money.

This is one of the more curious phenomena about education and it is also something I have reflected on quite a bit relative to my own journey to bitcoin. I went to Duke University in Durham, North Carolina and received an economics degree. Classically trained in Keynesian economics and having studied accounting and corporate finance, I do not recall any course work or lecture on Austrian economics and without doubt, I never learned anything about the history of money. After graduating, I went to work at Deutsche Bank in the Mergers & Acquisitions group, high finance at 60 Wall Street, just down the actual road from the New York Fed. In hindsight, I like to think that I was perfectly predisposed to reject the idea of bitcoin being viable as money as well as the basic tenets of Austrian economics. Both were an athame to everything I had learned in my early and formative years, from academics to my professional career and what it had taught me about the way the world worked and the incentives.

Ironically or not, the one thing I remember, as if it were yesterday, from my years in college was an economics professor saying, “we don’t teach you what to think, we teach you how to think.” I recall thinking that it was probably just a bullshit platitude but it did sound good.

And while I can’t recall anything tangible that I learned in college which meaningfully helped me in my professional career, it might just have been true after all. A few years after starting at Deutsche Bank, the world began to fall apart. I had no conception of what was happening, but the financial crisis was real. I also had a front row seat. It felt like being in a circus and while I may not have understood what was happening around me or why, I knew something was broken. I remember observing from the floor a cabal of the most senior M&A professionals in the bank huddled in the group head’s office, discussing as I soon found out bailouts for (or mergers with) various other banks leading up to the failure of Lehman Brothers. Comical really, now knowing that Deutsche Bank might be one of, if not the most, financially problematic and systemically important of global banks.

I might not have known “the why” at the time, but I did know something was broken. And, I will always remember that image of bankers huddled on the 45th floor of 60 Wall, in that time and place. It certainly stuck with me nearly a decade later as my journey began to bring me back full circle. In 2016, I set off to understand what had caused the great financial crisis.

It was research in furtherance of my then role at a hedge fund in Dallas, but also, it was always a curiosity of mine. What actually caused the chaos I lived through a decade prior, but did not, and really could not, understand? Around the same time and coinciding with this research, I was also asked to do due diligence on a company in Canada that led to my paths crossing with Saifedean Ammous, author of the Bitcoin Standard and a contributor to this edition of the Bitcoin Times. It was these pursuits and circumstances that ultimately put me at the doorstep of bitcoin and my first introduction to Austrian economics. It also informed my conclusion that what was broken was the money and that nothing could really be fixed until the money itself was.

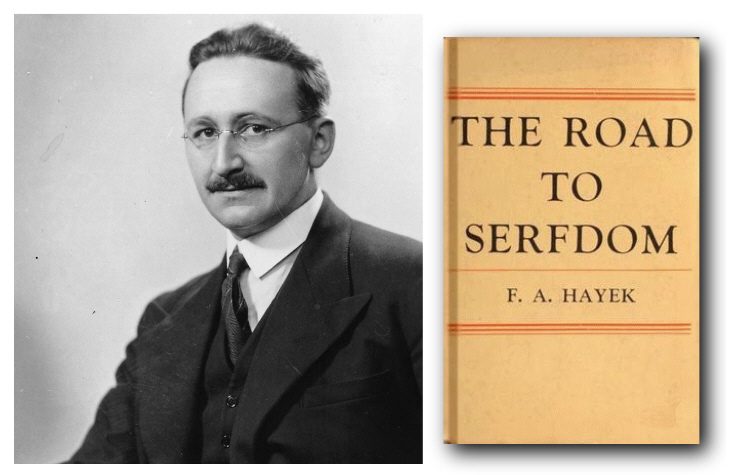

Saif helped me understand what money was, and how it had evolved through history. While he had not yet penned the Bitcoin Standard, Saif laid the foundation for me to understand economics in a way that I was not taught in school. He specifically helped me understand monetary economics and introduced me to Austrian economics. I read the Road to Serfdom by Fredrick Hayek, the Reader’s Digest version published around World War II, which as an aside was tailored to an American audience and decidedly distinct from the first English edition.

While better read and more learned disciples of the Austrian school might discount Hayek, believing him to have compromised on certain important principles, he was a disciple of Ludwig Von Mises and there was truth in his works that helped me understand how the world worked in a way that I did not gather from my time studying economics in college. The Road to Serfdom, which Hayek dedicated to ‘the Socialists in all Parties,’ made the best fundamental case of which I have ever read as to why collectivism fails and ultimately leads to economic ruin.

It also explained in a rigorous and logically-ordered way why socialism inevitably leads to authoritarianism and tyranny, and similarly ends in economic and humanitarian ruin. Many ideas clicked for me but particularly the ones centering on the function of money and the consequences of socialism and collectivism to the pricing mechanism which coordinates economic activity. The Road to Serfdom made clear just how important the pricing mechanism is to an economy as well as why it breaks down as the control of resources centralizes.

Later I read two additional resources by Hayek, which further distilled my understanding of the pricing mechanism and the consequences of centralized management of the economic system – The Use of Knowledge in Society and the Pretense of Knowledge, the latter being the text of a speech Hayek gave in acceptance of a Nobel Prize.

In The Use of Knowledge in Society, Hayek described the pricing mechanism as one of the greatest triumphs of the human mind; it just wasn’t invented by deliberate design and its significance does not get near the attention it should by those who seek to manipulate it via central command, likely for the reason that it was not engineered by conscious control.

In the Pretense of Knowledge, Hayek articulated the fundamental reason why the manipulation of the money supply creates sustained economic imbalance and more acute longer-term unemployment, while also cutting the Keynesian “aggregate demand” theory as a target to achieve “full” employment at its knees.

Through these works, I began to build a knowledge base that argued fundamentally against everything I had learned in school – which was built on a foundation that assumed active management of the money supply and government spending was a net benefit to society as a starting point. It was text books and academics versus real world experience and common sense. Had I assumed what I had learned in college to be true, I would have rejected Hayek and the tenets of Austrian economics as naïve. Instead, I questioned it critically and evaluated which ideas were anchored in first principles, and which were more true based on my real world experience. Maybe I did learn how to think rather than what to think after all.

Through this process of learning and reflection, I began to understand price as only existing as a phenomenon of mass convergence on a common form of money. And to be clear, I’m not making reference to price in the simplistic context of “CPI” or your standard econ 101, “theoretical” supply and demand equilibrium chart of a single good. Instead, the idea that value itself in quantifiable form or any broad-based price system would not exist if not for a market economy converging en masse on one form of money. Without a common form of money through which to value other goods, there would be no concept of price; at best, there would be exchange ratios between commonly traded (or bartered) goods.

10 apples equaling 1 chicken is an exchange ratio, not a price. the price of a chicken being $10 and the price of an apple being $1 implies the exchange ratio but from where and how did price and the pricing mechanism emerge? Price and a pricing system was the derivative output of convergence on a single form of money (i.e. the pricing mechanism). Money is the thing assumed as given in all economic textbooks. However, money itself is not explained. The very thing upon which every economic calculation is based is a phenomenon of profound consequence yet no one really questions how it emerged, why it emerged or maybe most importantly, why money converged (or converges) to one.

I introduce this concept as a preamble to the Bitcoin Times Austrian Edition because it ultimately allowed everything else related to bitcoin to fall into place; the pricing mechanism and price as a system was the key. It also provided me with a foundation to more critically evaluate the economic principles I learned in college, ultimately accepting the Austrian school, which I was not taught, over the “classical” Keynesian and Monetarist theories which I was. Most important of my conclusions might all be summarized in two simple quips. (1) it’s the pricing system, stupid! And, (2) don’t fuck with the money.

At the start, I explained that the hardest thing to understand about bitcoin had little to do with bitcoin and everything to do with money. These days, when I explain bitcoin to anyone willing to listen, I tell them that if there were one thing to remember it would be this – all fundamental value in bitcoin derives from the fact that there will only ever be 21 million. And, that if bitcoin credibly enforces its fixed supply of 21 million, then bitcoin would emerge as the global reserve currency (almost definitionally).

In my view, bitcoin’s zero to one innovation is finite scarcity because it represents the foundation of the world’s new monetary system and consequently its emergent pricing mechanism. Simply put, bitcoin is a form of money that cannot be printed and that is not just sufficient to create the possibility of global adoption, it will functionally cause it.

Wrapped up in this conclusion are two critical economic principles. First, there is a form of money with an optimal supply and it is the one with the lowest rate of change on an absolute basis. A form of money with a fixed supply has a terminal rate of change (in supply) of zero, which is the lowest absolute change possible. A form of money which cannot be printed (at all) is better than any other form of money whose supply is susceptible to increases or decreases, arbitrarily or otherwise. Always apply the common-sense test. Would you rather be paid in a form of money that can be printed or not? The answer is obvious and I find it to be far more intuitive than the second principle, which is as follows – money converges to one medium based on the nature of money and the very problem which money helps to solve, namely the facilitation of trade (or exchange), which is an inherently intersubjective problem. The evaluation of bitcoin and money, more generally, would be a turtles-all-the-way-down dilemma if not for this fact.

Humans need money to survive just as they need water to survive; it is actually money that coordinates trade to deliver water to billions of people. The underlying principle is that humans benefit from cooperation via trade and that the benefits from trade are not zero-sum. The benefits from trade are positive-sum, but in order to scale trade, specialization and the division of labor, money as an economic good is a necessity. In order for any two people to effect trade with money, both would have to have first formed a consensus as to the form of money with which to use. In short, I would need to have the form of money you were willing to accept in order for us to trade. It is an intersubjective problem for that reason and the evaluation is both objective and relative to all other possible forms of money. It is also not a coincidence, belief system or collective hallucination as to how we (you and I) arrive at the consensus. There might be many inputs to the evaluation but inevitably, everyone arrives at the objective conclusion that the best form of money would be one that is hard to produce, with the hardest to produce being the one that cannot be produced at all (let alone printed).

And, if you evaluate the dilemma between any two trading partners and then extend it to the third trading partner, the fourth or the fifth, you will realize that the problem is identical and extends to all eight billion people in the world. Everyone has the same problem and everyone has an incentive to hold the best form of money. By holding (or trading for) the best form of money, it will result in the widest range of trading partners and ultimately the greatest range of choice and the greatest positive sum benefit to each individual who holds the currency.

Now, if any individual evaluates these two principles and comes to the conclusion that there is an optimal state, that it is the form of money that cannot be printed and that money converges to one, it is highly likely that individual will begin to seek out the best form of money because it will be the one that the most people will accept in the future. Because the evaluation is objective, the logical and inevitable conclusion is bitcoin for the principal reason that, in a terminal state, it cannot be produced by anyone or at all. As each individual goes through this process, consciously or subconsciously, an emergent consensus will continue to form. As a critical mass is established, only then can a price system emerge. Price is an output of the adoption of a pricing mechanism, which is the money objectively evaluated in the market. Arrive at the conclusion that a price system emerges as a function of the use of one single and common form of money, contemplate its consequence and accept that it does not occur by coincidence and you too will be at the doorstep of bitcoin adoption.

Recognize that human beings cannot conceive of a world without price; food, gas, rent, cost of a home, mortgage, phone bills, the internet, healthcare, water, power, travel, education, retirement, etc. Each individual likely does hundreds, if not thousands, of economic calculations each day, even if they might not know it consciously; every economic opportunity cost and trade-off, including the evaluation of time itself, is anchored to the price system and the pricing mechanism. And, there would be no concept of price if people did not first converge on the common use of a single form of money. Explain to yourself the why behind the fact that you and 99.9% of all people on earth only interact with a single form of money on a daily basis and inevitably you will come to the profound significance and consequence of the price system. It will also become your anchor point as to why bitcoin is emerging and will continue to emerge as the single form of money everyone will commonly accept in the future.

Price is a communication of preference and changes in price are changes in preferences, each valued and expressed through money, by and between everyone in an economy, individually and collectively down to the money and pricing mechanism itself. It is the output of the most complex system one could possibly imagine. Not only did this help me understand why the world converges on a single form of money for very necessary and objective reasons, but it was also this that helped me understand the Austrian way of thinking. The contrast between the Austrian school and all others is that the Austrian school attempts to explain incentives and describe why the world works the way it does down to individual decision points rather than focusing on aggregates. The price system tracks, communicates and describes these individual decisions as well as the aggregate of individual decisions; attempting to understand and interpret this behavior is enough for the Austrians. In contrast, Keynesian et al. economists attempt to use a form of pseudo-science to predict and influence aggregate outcomes, using top-down levers and the aggregates themselves as inputs, ultimately distorting the price system.

There is a critical difference between measuring aggregates and using those aggregates as inputs to centralized economic decisions, such as active management of the money supply or using government spending as a lever to alter business cycles. It is the equivalent to the circular reference error in excel. And importantly, if prices are the communication of preferences of those that make up the economy and who possess the skills to actually produce real goods and services, price targeting and the manipulation of the pricing mechanism distorts and put at risk the entire economic foundation, while also working in direct opposition to those in the market who are setting prices (and value) in the first place.

On my own journey, I ultimately came to the conclusion that centralized manipulation of the pricing mechanism causes far ranging, negative and impossible-to-quantify or predict consequences. Impossible by definition as the complexity of the price system extends far beyond the conscious control of any individual or group of individuals. It is the folly of Keynesian and Monetarist economics. High degrees of centralization, both of the money system and through the expansion of government budgets, ultimately destroys the pricing mechanism entirely, especially when trillions upon trillions of dollars are created out of thin air.

Printing money impairs the pricing mechanism by distorting every price in the world and not equally; expanding government budgets consolidate the pricing function into fewer and fewer hands and away from those with actual skills and knowledge in the real economy to deliver goods and services. Over time, imbalances grow through this process, and the price mechanism degrades until it becomes so impaired that it is no longer functional in coordinating trade and economic activity, which is what causes hyperinflation. This does not mean all function of government is necessarily bad. But, it does mean in an absolute sense that the manipulation of the money supply, which itself creates the opportunity for the unrestrained expansion and centralization of government, is in each and every sense extreme in its negative consequence, and bitcoin eliminates that ability completely.

After arriving at these conclusions, I came across a book called Keynes | Hayek, The Clash That Defined Modern Economics. By this point, I had read both Hayek and Keynes but I did not realize the two were contemporaries who actively corresponded, challenging each other’s ideas in real time. I had read them each on the merits of ideas and not in the historical context that there was an active and ongoing debate in the early to mid-twentieth century.

The Keynesian view won out, not in the end but at least for the time and I also understood why the two worldviews could not co-exist. Each functionally argued that the other was foundationally errant. This is how I have come to explain why mainstream economic circles, including the whole of western universities as well as modern central banks, have necessarily become a monoculture. Either you believe there is net benefit to manipulating (or actively managing) the money supply and derivatively using unfunded government spending to influence economic outcomes (and to distort the economic pricing mechanism) or you do not. While the debate between Keynes and Hayek was just that, a debate, and while the theoretical or actual debates between any of the authors in this Austrian edition of the Bitcoin Times and the likes of Janet Yellen, Paul Krugman or Stephanie Kelton would be the same, the beauty of bitcoin is that it is not a debate. Instead, it is a market test.

There are two economic systems competing with each other. The one of the old world, of dollars, euros and yen built on the foundation of the Keynesian view. And, the one of the new world, built on bitcoin and one inherently of the Austrian view. No longer do we have to resort to intellectual debate of who is right or wrong. For the first time, there is a market scorecard and everyone has a choice. Each economic actor has the choice to either voluntarily opt-in to bitcoin or remain with the old guard. Over time, the view most correct and founded in first principles, will win. Each person that evaluates the questions as to what money is and whether bitcoin is money or not, is participating in this market test. As more people evaluate these questions and adopt bitcoin as a monetary standard, the true test of history will be had.

While the only test that matters in the end will be decided by the market, it is the ideas in publications such as this which will influence the outcome. This edition of the Bitcoin Times has contributions by three individuals who were formative in my own journey to bitcoin and Austrian economics (Saifedean Ammous, Pierre Rochard and Michael Goldstein) as well as three who I have come to know and respect, even if from afar, through their writing (Aleks Svetski, Konrad Graf and Rahim Taghizadegan). Collectively, these contributors lay out cases that range from bitcoin challenging the historical norms of how money is evaluated in the market, how money and time preference influence human action, how experience through trial and error outweigh all academic rigor as well as the parallels between the Austrian economic renaissance and bitcoin. Importantly, the authors discuss the origins, evolution and the importance of money, notably not to predict the future but to explain the world as it exists and why bitcoin is emerging as the consensus.

There is no doubt that the light dimmed on the Austrian school of thought in the second half of the twentieth century but it did not extinguish. Ideas that are true never do. Bitcoin, as an idea and tool, was the missing link to the Austrian renaissance and this collective work will inevitably spark renewed interest, not just carrying the torch forward but rekindling it. In aggregate, as is every version of the Bitcoin Times, the Austrian Edition is timeless. Most people will come to Austrian economics through bitcoin and this publication itself furthers that end. While the market test is the one that matters, the ideas shared by these authors will stand the test of time and I expect that for most early adopters, their understanding of bitcoin will necessarily be hardened and reinforced by the Austrian perspective on the world, especially those herein.

Finally, we have a sly round about way to fix the money and while history has not yet been written, this will inevitably be looked back upon as one of the formative pieces that made the connection between Austrian economics and bitcoin more apparent for the world to see and understand.

Parker A. Lewis, The future Mayor of Austin

Austin, Texas

November, 2022