From Bitcoin to the Austrian School, from the Austrian School to Bitcoin

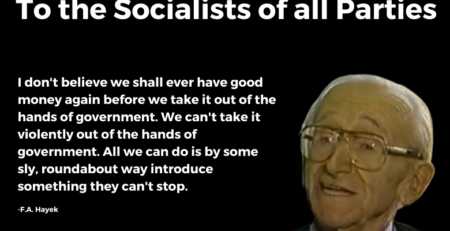

In the early days of Bitcoin, the Austrian School of Economics served as one of the entry points. Austrian economist Friedrich August von Hayek had even come closest to predicting Bitcoin. He imagined that a private money would be introduced in some sly and roundabout way, that government cannot stop because first, they ignore it, and then – after a period of rapid or exponential adoption – it is too late to stop.

Those well-versed in the writings of Menger, Mises, and Hayek had expected monetary competition to reemerge in a time of crisis. The Great Financial Crisis of 2008 seemed like a final vindication of Austrian Economics. Ron Paul became a household name in the US. Doubts about fiat dollars were at a peak. The time was ripe for change, but things quickly seemed to revert back to the status quo. E-gold, using a centralized ledger of gold claims, was shut down by the US government in 2009. Credit contraction was compensated by even more debt, in particular government debt, directly monetized through central banks. The societal conflict shifted from economics to politics again, and interest in the Austrian School was eclipsed by a new culture war.

Nowadays, the road goes the other way, from Bitcoin to the Austrian School of Economics, from the most exciting monetary experiment of our times to a niche tradition of thought. For some leftists peddling the kind of officially sanctioned conspiracy theories that do not get you canceled but nourish academic careers, the Austrian School is an immensely powerful force hidden in the shadows. They see Bitcoin as spawning from the same evil root as the Alt-right, Pinochet, Thatcher, Reagan, and everything else they dislike in the world. For most other academics, the Austrian School is relegated to a footnote in the history of ideas, an anachronistic tradition of which a few useful parts have been absorbed by mainstream economics, the remainder only being regurgitated by cranks.

The history of the influence and relevance of this tradition is in actuality, quite contrary to these misconceptions, and just as fascinating. Like Bitcoin, the Austrian School is at least three different and contradictory things: an asset, a network, and a movement.

Carl Menger revolutionized economics with a new approach to understanding value. Valuation is the subjective anticipation that the marginal unit of a good may serve as a tool to achieve an end. This end is subjectively ranked higher than alternatives in the same context and at the same moment. His approach is one of empathy, one that seeks to understand human beings with full appreciation of uncertainty and error. Menger was fully aware that the most profound error is the one committed by economists and other “scientists” who see themselves as betters who do not need to understand their subjects but only need to be understood and followed by them.

Likewise, the ideas in the tradition of Menger, and the whole concept of an Austrian School, are sought out by many people not as an end in itself, but as a means to further other ends. Ideas primarily serve as tools of rationalization, as labels and rallying cries for allies and filters for enemies, and as sources of credibility for our interests and preferences. The intellectual may be disheartened by this observation, but often overlooks the fact that the pursuit of ideas that lack any social utility turn out to be quite useful ideas for his own profession.

The Austrian School offers useful mental tools to understand our world, but only few care about that. Its usefulness as an asset, a tool to protect and further interests, comes from the standing, scientific merit, and persuasiveness of its proponents. Carl Menger had quite an extraordinary standing – as the tutor of the Crown Prince, one of the economists of the by now credentialed “marginalist revolution”, the youngest full professor at university, and the enabler of the highest worldly careers for his preferred students. Down the line, in the tradition started by him, even a Nobel laureate followed suit. Some odd professors, universities, institutes, and faculties today still academically engage in the Mengerian tradition.

If we apply the realistic method of the Austrian School to itself, we have to acknowledge that, for most people, it is a means to an end. Academic theory is foremost a game of credibility for elite or public persuasion. Similarly, Bitcoin is, to most people, primarily an asset, something bought for fiat dollars to appreciate in fiat dollars. Interest is mostly cyclical and follows the price action. That is not bad or evil, but all too human. Let us not mock, but empathize with the human need to protect and further our interests by seeking more useful assets and ideas.

However, Bitcoin is so much more than bitcoin, the unit of value, and its greatest value lies beyond the short-term instrumentality as a means to make more dollars. Likewise, the Austrian School is so much more than a sound and credible framework of thought and persuasion. Its true relevance for human wellbeing has been mostly invisible. Counter to some narratives pushed in the academic history of ideas, it has not been a conspiracy, not an organized elite project, but a spontaneous emergent order of thought and, more importantly, action.

Austrian Enlightenment

The Austrian School’s standing and instrumental value are almost as shaky as the dollar price of bitcoin. The Crown Prince had committed suicide. Menger’s students who had become ministers in government introduced taxes and regulations of the lesser-evil kind, administrative measures in the service of the state that were not outright socialism. The last full professor of the Austrian School in Vienna was a careerist, happy to get rid of Jewish competitors. The “Nobel Prize” for Friedrich von Hayek was actually a “Prize in the memory of Nobel”, funded by the Swedish central bank after Nobel’s death and against his will, to legitimize economics as a “science”. Hayek served as a fig leaf for co-laureate Gunnar Myrdal, a Swedish social engineer and proponent of a redistributive world government. To be fair, Hayek was the only laureate ever to criticize the prize and the intentions behind it.

Credibility can be consumed as status. Menger had highlighted the intricate and invisible capital structure enabling consumption. So, whence the status and impact of Menger? Like Bitcoin, the Austrian School is, more importantly, a distributed network, with its “consumables” as tips of the hidden icebergs of capital structures. Carl Menger was one of the brighter nodes in a fascinating network of thought that was spun in an ever more connected world.

The exponential and disruptive increase in productivity through capital reinvestment was spreading in Europe. Austria-Hungary was a latecomer to Western modernity. Its ethnic, religious, economic, and cultural diversity was at odds with the latest political fashion of centralized nation-states feeding on the financialization that accompanied top-down industrialization. The intellectual connections, formerly restricted to a small polyglot elite, intensified and became accessible to more and more people through railroads and automated printing presses.

In 19th- and early 20th-century Vienna, the empire’s political, intellectual, and financial center, the acceleration of connectivity, network effects, and societal complexity turned out to be too much for many people. It was an age of “neuroses”. The economic ills due to increasing consumerism and credit expansion receded behind the psychological ills. It is no surprise that there emerged at least three “Viennese Schools” of psychology. The counter-reformation had tried to bring back cohesion to a society in turmoil, but even more than politicizing religion, it pushed heresy into political thought. For a while, a young Hitler, Stalin, Trotsky, and Tito idled in Viennese coffee shops.

Out of this sentiment of crisis, a little understood Austrian Enlightenment had emerged. Austria had had its run of continental top-down enlightenment by “enlightened” Joseph II in the 18th century. Against the artificially and selectively pushed “modernization”, combining the counter-reformation with a top-down reformation and nationalization of monasteries, the bourgeoisie sought refuge in the culture of “Biedermeier”. It is ridiculed today as a nostalgic and romantic phase of apolitical distraction but compares favorably to the later politicization of democratic “citizens” and their impatient lust for the new, “original” and bizarre to find distinction among alleged equals.

The Austrian monarchy was still less modern than other political structures in Europe. Whereas the more progressive Prussian bourgeoisie identified with a centralized nation-state and was filled with enthusiasm about noble careers for commoners in the navy or academia, Austrian commoners, in particular those drawn to the center by economic opportunity, had to canalize their energy and attention more in culture and enterprise than in politics. The resulting cultural tone and vibe were starkly different. Austrian writers of the 19th century show more irony; the mood is more down-to-earth, with more appreciation for details and flaws, whereas the Prussian mood was one of epic self-righteousness.

In the Austrian empire, a limited group of merchants had been granted total economic freedom and tax exemptions to make up for the relative backwardness of the empire. Successful entrepreneurs gathered in Vienna, and their quickly rising wealth brought leisure without political clout, influencing, among others, people like Menger and Hayek.

In a way, they resembled the Scottish Tobacco merchants whose leisure and similar distance from the state had fostered the Scottish Enlightenment. And there had indeed been old intellectual connections through Scottish and Irish monks and the scholastic tradition. More importantly, 19th century Vienna had shown similar network effects of thought, giving rise to dozens of Viennese or Austrian Schools with world-leading scholars in almost every discipline.

The word “school” derives from the Greek word for leisure. In this context, it denotes the remarkable spatial and temporal concentration of profound thinkers with an impact on their societies. It was a short phase of relative economic and intellectual freedom, where growing wealth supported productive instead of consumptive leisure. In the coffee shops and salons of the time, the best and brightest connected, built upon each other’s work, and took delight in understanding the complexity of society rather than dissecting it to “remold it nearer to the heart’s desire” as the later English followers of hybris and top-down “enlightenment” – the Fabians – would attempt.

Top-down “enlightenment”, in particular the French one of the “philosophes” and Jacobins has been the more visible and prevalent reaction to the increased dynamics and complexity of European societies. It is the reaction of the educated, whose heads are filled faster with grandiose ideas than their life can afford any attenuating practical experience. It is the impatience of betters with the “ignorance” of the common man. It is hybris, the pride of those who like to play God and lust to be worshiped. A reaction against this pride often turns common men against ideas and change, toward longing for a romanticized past of an innocent childhood of men, but will only deliver them to other political grifters, feeding on artificial discord.

That other kind of enlightenment, of the Scottish or late-Austrian sort, a camaraderie of sovereign individuals “emerging from our self-incurred immaturity” in an act of courage, motivated the likes of Menger and Mises. The latter’s motto was “do not give in to evil”. His “Mises Circle” would become the pinnacle of the Austrian School as a network, a private salon attracting the greatest minds not only of diverse academic disciplines but also of entrepreneurship and culture. Ludwig von Mises did not teach monetary theory, did not ‘school’ anyone, imposed no line of thought, but mostly debated epistemology – the question of how knowledge is possible in an age of uncertainty. One of the participants of the Mises Circle was, for example, Eric Voegelin, who would establish the “theology of politics”, showing how ideology tends to fill a religious vacuum and how the most secular “evidence-based and scientific” modern political thinkers are actually Gnostic zealots in disguise.

Ideological nonsense would tear Europe apart, culminating in a 20th-century secular version of the Thirty Years’ War, almost as destructive. Menger saw it all coming, and his gloomy outlook may have affected the Crown Prince. Mises was high on the list of the Nazi’s main intellectual foes. They tried to kidnap his wife to bring him back from his Swiss refuge and had his apartment raided, and his personal library confiscated on the day of the “Anschluss” (annexation) of Austria to the German Reich. Curiously, his lost library reappeared decades later in a secret Soviet archive.

Carl Menger never finished his planned theoretical masterwork. Like most important members of the Austrian School, he doubted that economics made sense as a separate “scientific” discipline. He would have preferred the term “sociology”, but it had been taken over by the French tradition of Utopian social engineers. He advised his two favorite students not to pursue an academic career.

Those two lesser-known nodes in the network of the Austrian School would go on to have a much more profound impact on the world than the academic heirs of that tradition. Felix Somary turned out to be even more prophetic than his teacher, and was later called the Raven of Zurich by his contemporaries. He would become one of the founders of Swiss private banking, a privacy-protecting financial infrastructure, underestimated in its importance for the 20th century. The other student was Richard Schüller, one of the best-connected diplomats of his time, who played an equally underestimated role in the return to peace after the World Wars and the independence of small post-war Austria.

Since the early days, the Austrian School has inspired a huge network of practical and private people, entrepreneurs, diplomats, innovators, and investors, and it still does. In this sense of a network, Satoshi Nakamoto obviously belongs to the Austrian School – not only being inspired by its monetary and business cycle theory, but himself contributing even some theoretical insight on the difficult question of the “regression theorem”, overshadowed, of course, by his giant practical contribution. How curious that he chose a Japanese moniker, given that Carl Menger’s library has ended up in Japan.

A network does not only connect but may assume a life-like quality of “increasing returns” and positive network effects of symbiosis, cooperation, and flourishing. Like the Austrian School in its heyday, the network of thinkers who are curious about Bitcoin and appreciate its complexity, in contrast to the academic dimwits telling us why it is broken, will fail, and that only they can fix it, begins to show a similarly enlightening dynamic. It may become the network attracting the brightest and deepest minds of our age and usher in a new Enlightenment or Renaissance. But let us not get ahead of ourselves too much.

A Living Movement.

Like Bitcoin, the Austrian School is a third thing, totally different from the two I have described above. It is this last aspect that mainly attracts new proselytizers. The Austrian School, like Bitcoin, is also a movement. It has become a movement in its exile in the United States. The Mises Circle and the Mises Caucus are obviously very different things of very different people, serving very different ends.

Menger and Mises had preached value neutrality. They taught seeking to understand first before you judge. They eschewed politics. Obviously, they were not nihilists, but staunch defenders of values they saw as crucial for human flourishing. Mises, in Vienna, the humble salon host and neutral advisor, had a more important role to play as a champion of liberty in the United States. Mises and Hayek realized that the value-neutral understanding of the complex problems of exchange and production in society would not suffice to understand the dangers confronting civilization. Out of the most affluent and enlightened societies, the most demonic tendencies emerged. The dream of reason could and would produce monsters.

Carl Gustav Jung, a student of Sigmund Freud who revolted against his teacher, had started to look for hints in the unconscious, in dreams, lore, and faiths, for a demonology of modern politics. Oddly enough, when writing a little on economics and money, he sounded like an Austrian economist. Even more oddly, modern Jungian Jordan Peterson has discovered his connection to the Austrian School, without conscious knowledge of the historical links.

Viktor Frankl, the proponent of the second Viennese School of Psychology, pointed to the existential vacuum and longing for meaning of modern man as important hints for understanding the demons of modernity. Eric Voegelin, and Murray Rothbard without having read Voegelin, both realized that the most demonic ideologies shared the common trait of secular eschatology. They renounce the real world and real man as wicked and try to hasten a purging apocalypse, bringing about a millennial empire of perfect justice.

This kind of evil cannot be refuted, but has to be fought. It may lurk deep in our unconscious as Thanatos, the death drive. Frankl had observed that true liberty is costly; its price is responsibility. If we reach for the stars, for the pinnacle of our human potential, we cannot always count on our instinct or our traditions to tell us what to do. Therefore, most people look around nervously and do what everyone else is doing, support the current thing and seek safety in numbers. For some – the proudest and the most antisocial – this is not enough. Where we see complexity, they see chaos. If the world and their mental schemes do not align – the worse for the world. They prefer to impose a deadly order than respect a living order they cannot understand, design or rule.

“It consumes energy,” they exclaim with exasperation, and the implicit thought continues, “I have neither granted it this energy nor do I understand, let alone appreciate its existence. Smash it!” They despise any complex and dynamic structure, any organism, that is not accessible and amenable to their imaginations. It is against this death drive that Hayek proclaimed his allegiance to the “Party of the Living”. How curious, that Bitcoin and the Austrian School can also be understood as movements, fighting on the same side, without diminishing their more open character as networks and more useful character as tools.

Rahim Taghizadegan

September, 2022