Bitcoin and The Hopf Cycle of the Internet

It Always Starts With A Meme

An interesting meme has been circulating on the Internet over the last few years (at least). The words used for the caption come from the 2016 post-apocalyptic science-fiction novel “Those Who Remain”, by G. Michael Hopf.

Two of the pictures used actually come from the 1833–1836 series of paintings “The Course of Empire”, by Thomas Cole:

The meaning of the paintings themselves are very similar to the meaning of the meme, surprisingly. Or perhaps unsurprisingly, since many artists, philosophers, and even historians throughout the centuries have expressed the same concept, or concepts.

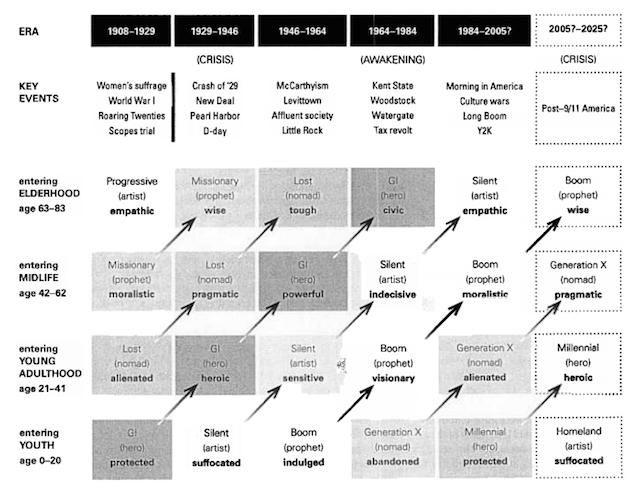

Another famous example would be the Strauss–Howe generational theory:

Indeed, Hopf’s phrasing is just the more recent (and possibly more effective to date) expression of some kind of very ancient intuition about a particular kind of social (but possibly even biological) feedback loop, deeply connected with the ideas of natural selection and antifragility:

- Bad Times create Strong Men

Complex systems tend to strengthen when they survive traumatic events, evolutionary bottleneck, crises; - Strong Men create Good Times

The new level of strength tends to move the system away from the previous stress-factors, into a no longer traumatic equilibrium; - Good Times create Weak Men

The new low-stress equilibrium tend to select for new traits which are not optimized for stress-resistance (centralization, specialization, growth, and convenience replace decentralization, redundancy, reparation, and security); - Weak Men create Bad Times

The “atrophy” of some of the system strength, plus the concentration of systemic risks, increases the probability of new crises, new traumatic events, and so on.

While simple and exact predictions about complex systems are by definition difficult, and while too strict an interpretation of these “rules” tend to degenerate into pseudo-scientific models, implausible variants of historicism, cheap moralistic mantras, and unsubstantiated urban legends, it’s difficult to deny the fundamental nature of similar feedback loops, in a general enough interpretation.

Internet Memes Applied To The Internet

It could be interesting to try and apply this model to the Internet itself, and see if we can get any suggestion out of it for the technological tools that have been developed during the last half of a century, and for the ones that are being developed now, particularly in connection with Bitcoins.

“Hard Times create Strong Tools.”

It should be uncontroversial to state that the invention of the TCP/IP protocol suite, with its fundamentally decentralized and “apocalypse-resistant” design, was at least partially driven by the adversarial mood caused by the Cold War, and the pervasive nuclear scare.

Much has been written about the fact that the specific goal of the “Arpanet” research project was actually different from the survival of the network to the nuclear holocaust. And it’s also true, following Bastiat, that “what is seen” in terms of politically-driven investments, in the context of government-sponsored programs, hides “what is not seen” in terms of missed opportunities and alternative allocations of the same resources (translation: it’s not impossible that we may actually have a better Internet, today, if the Cold War and the DARPA agency didn’t even exist in the first place). Nevertheless, it’s clear that the particularly “hard” times surrounding the inception of the Internet contributed to some of its objective strengths.

“Strong Tools create Good Times.”

It’s arguably fair to state that the general optimistic mood which characterized the end of the twentieth century was at least partially driven by the success of the Internet in connecting the world. While most of the reasons for talking about the “end of history” were geo-political in nature (the collapse of the Soviet Bloc and the so-called “Pax Americana”, which was not without its fair share of sanguinary wars), technological tools were also instrumental for the creation of that triumphant exuberance: the commercialization of the Internet, following the December 1994 release of Netscape Navigator and the NSFNET selling all its assets in 1995, generated huge expectations. Soon enough the entire financial market was cannibalized by the so-called “dot com” bubble in the late ’90s. The rate of technological and scientific innovation accelerated hugely, and the wave of “Internet Optimism” overflowed from the stock market into culture, literature, art, entertainment, and society in general.

“Good Times create Weak Tools.”

With the new millennium, the “dot com” bubble finally burst, but the Internet was here to stay, changing the world economy and our lives for good. From the ashes of many shameless money-grabs, actual technological giants emerged, replacing most consolidated industries at the top of the stock markets and shaping the “new economy”. But the lazy reliance on convenience and trust and the absence of adversarial thinking contributed to the weakening of the Internet infrastructure. Everything became more centralized and trust-based, thus more efficient, but also more fragile.

We can find many examples in the tools we use every day: while the SMTP protocol is theoretically still decentralized, most of us now completely depend on services like Gmail. The same goes for ISP concentration, DNS bureaucratization, centralization of localization services, etc. This trend produced even more extreme effects after the “cloud-computing revolution”, when even big companies (let alone individuals) stopped hosting servers and just began to use a few cloud providers, and after the “social-network revolution, when most of the world population started to see the mobile apps provided by a few proprietary platforms as “the Internet”.

This process was the result of many individual choices that were “locally rational”: network effects are very strong, especially for services leveraging “social networks”, and technological centralization makes most services more efficient, fast, cheap and convenient!

Everybody can immediately appreciate these advantages, while the attached costs may only become apparent after many years: it’s a matter of what economists call “time preference”.

“Weak Tools Create Bad Times”

This centralization process was not without advantages. A lot of people have access to the Internet today, even in the most remote places. Even people who could be considered deeply impoverished have smartphones. Everything is faster, cheaper, and simpler than ever, with more and more features accumulating every year. But all this came with a cost. Centralization usually brings along serious risks of monopolization, corruption, exclusion and abuses. Indeed, today we are very easily censored, blacklisted, tracked, spied upon and watched every time we use the Internet. The political risk of scary Orwellian drifts is not even theoretical anymore: we really live in a world where crime-exposing journalists like Julian Assange, or peaceful e-commerce innovators like Ross Ulbricht, are literally imprisoned (often for life, and often employing methods that resemble torture very closely) for the way they used the Internet. While almost everybody has a smartphone, almost nobody is free to use it in a secure, open, unrestricted, and privacy-preserving way, and most people are excluded from the Internet-based commercial and financial infrastructures due to “KYC” political restrictions.

Lessons for Bitcoin

The circle closed again: Bitcoin, which can be considered the “value layer” of the Internet (even if it represents in some sense an innovation which is way deeper than the Internet itself) has been created to mitigate and overcame these “Hard Times” made of Internet censorship, digital surveillance, financial exclusion, virtual money-manipulation.

Bitcoin not only can, but it must, learn the lessons that the partial centralization of the Internet have taught [some of] us. By learning from the past, we can avoid similar traps, and could go a long way toward also helping “re-decentralizing” the whole Internet infrastructure again. It could go either way: we could either move to a world where Bitcoin-based permissionless micro-payments and Bitcoin-inherited security mindset allow us to create a network of decentralized, trust-minimized and privacy-respectful systems for storing, transmitting and computing information, or we could see Bitcoin getting more and more centralized, intermediated, regulated, manipulated, corrupted, censored.

This means recognising there are no panacea solutions. Only solutions with inescapable trade-offs. As a result, we need to act accordingly and focus on security, privacy, and verifiability first, over convenience, comfort, “user experience” and compliance (which are all nice things to have, if and when possible), and this needs to be done at all levels, ie; as users, as developers or service providers.

From the user point of view, trusting third-party custodians like MtGox, instead of bothering to learn private key management, is convenient, but fragile. Trusting ASIC-production monopolists like Bitmain (via “SPV” clients), instead of bothering to run a full validating node, is convenient, but fragile. Trusting tax-lawyers and security guards to protect us from legal confiscation and casual kidnappings, instead of bothering to learn privacy best practices (Tor, CoinJoin, UTXO management, KYC-avoiding, etc), is convenient, but fragile.

From the developer or provider perspective, trust and centralization are obviously easier to monetize (how do you charge for open source, decentralized, trust-minimizes protocol?). But again, they are fragile.

The current relics of “Good Time mindset” make it difficult to understand the trade-off, but Bad Times are coming again to remind us of the price we may pay in the long run for our convenience in the short run.

It’s time to build Strong Tools again.

Giacomo Zucco

Nov 2020